Rudyard Kipling was an Englishman born and raised in India during the second half of the 19th century. He became a writer for Indian magazines at an early age and soon after, began writing stories about his travels and experiences in the Indian interior. He is most famous for his novel, "The Jungle Book" as well as his short stories, such as, "Riki-Tivi-Tavi".

Rudyard Kipling was an Englishman born and raised in India during the second half of the 19th century. He became a writer for Indian magazines at an early age and soon after, began writing stories about his travels and experiences in the Indian interior. He is most famous for his novel, "The Jungle Book" as well as his short stories, such as, "Riki-Tivi-Tavi".But, what is little known about this historic writer is his travels to America. In March 1889, at the age of 23 and before his international recognition, he sailed from India, through Southeast Asia and landed in San Fransisco on a legendary journey through the American continent. From San Fransisco he headed north, through Oregon and Washington, then up to British Columbia. The notes and remarks that he has about the Cascadian region are undoubtedly interesting.

There is nothing like an outsider's perspective to really understand the history of a place. Kipling dissects the Northwest like an anthropologist, pointing out all of the quirks that make up this region and its people. I would highly reccommend a read, of the whole book, Sea to Sea, but for now you can enjoy some of these great excerpts about Cascadia and its history. Enjoy!

In the late 19th century, salmon fishing was still an incredibly popular and lucrative job. Here, Kipling writes to Indian fishers about the unbelievable abundance of fish in the Northwest:

In the late 19th century, salmon fishing was still an incredibly popular and lucrative job. Here, Kipling writes to Indian fishers about the unbelievable abundance of fish in the Northwest:I HAVE lived! The American Continent may now sink under the sea, for I have taken the best that it yields, and the best was neither dollars, love, nor real estate. Hear now, gentlemen of the Punjab Fishing Club, who whip the reaches of the Tavi, and you who painfully import trout to Ootacamund, and I will tell you how “old man California” and I went fishing, and you shall envy. We returned from The Dalles to Portland by the way we had come, the steamer stopping en route to pick up a night’s catch of one of the salmon wheels on the river, and to deliver it at a cannery downstream. When the proprietor of the wheel announced that his take was two thousand two hundred and thirty pounds’ weight of fish, “and not a heavy catch, neither,” I thought he lied. But he sent the boxes aboard, and I counted the salmon by the hundred—huge fifty-pounders, hardly dead, scores of twenty and thirty-pounders, and a host of smaller fish.

From Portland, Kipling decided to take a little fishing trip of his own on the Clackamas River. The insurance man, "Portland", had gotten him a team and crew together for the short journey, but inevitably, it was not quite up to the standards that Kipling expected:

The team was purely American—that is to say, almost human in its intelligence and docility. The bystanders overwhelm[ed] us with directions as to the sawmills we were to pass, the ferries we were to cross, and the sign-posts we were to seek signs from. Half a mile from this city of fifty thousand souls we struck (and this must be taken literally) a plank-road that would have been a disgrace to an Irish village. All the land was dotted with small townships, and the roads were full of farmers in their town wagons, bunches of tow-haired, boggle-eyed urchins sitting in the hay behind. The men generally looked like loafers, but their women were all well dressed. Then we struck into the woods along what California [a guide] called a “camina reale,”—a good road,—and Portland a “fair track.” It wound in and out among fire-blackened stumps, under pine trees, along the corners of log-fences, through hollows which must be hopeless marsh in the winter, and up absurd gradients. But nowhere throughout its length did I see any evidence of road-making. There was a track,—you couldn’t well get off it,—and it was all you could do to stay on it. The dust lay a foot thick in the blind ruts, and under the dust we found bits of planking and bundles of brushwood that sent the wagon bounding into the air. Then with oaths and the sound of rent underwood a yoke of mighty bulls would swing down a “skid” road, hauling a forty-foot log along a rudely made slide.

Eventually they did make it to the Clackamas and here the scenery was a bit more tranquil:

That was a day to be remembered, and it had only begun when we drew rein at a tiny farmhouse on the banks of the Clackamas and sought horse-feed and lodging ere we hastened to the river that broke over a weir not a quarter of a mile away. Imagine a stream seventy yards broad divided by a pebbly island, running over seductive riffles, and swirling into deep, quiet pools where the good salmon goes to smoke his pipe after meals. Set such a stream amid fields of breast-high crops surrounded by hills of pine, throw in where you please quiet water, log-fenced meadows, and a hundred-foot bluff just to keep the scenery from growing too monotonous, and you will get some faint notion of the Clackamas. How shall I tell the glories of that day so that you may be interested? Again and again did California and I prance down that reach to the little bay, each with a salmon in tow, and land him in the shallows. Then Portland took my rod, and caught some ten-pounders, and my spoon was carried away by an unknown leviathan. Very solemnly and thankfully we put up our rods—it was glory enough for all time—and returned weeping in each other’s arms—weeping tears of pure joy—to that simple bare-legged family in the packing-case house by the waterside.

Next Kipling's American guide, California, took him North to see the boom town of Tacoma:

Next Kipling's American guide, California, took him North to see the boom town of Tacoma:California was right. Tacoma was literally staggering under a boom of the boomiest. I do not quite remember what her natural resources were supposed to be, though every second man shrieked a selection in my ear. The rude boarded pavements of the main streets rumbled under the heels of hundreds of furious men all actively engaged in hunting drinks and eligible corner-lots. They sought the drinks first. The street itself alternated five-story business blocks of the later and more abominable forms of architecture with board shanties. Overhead the drunken telegraph, telephone, electric light wires tangled on the tottering posts whose butts were half-whittled through by the knife of the loafer. Down the muddy, grimy, unmetaled thoroughfare ran a horse-car line—the metals three inches above road level. Beyond this street rose many hills, and the town was thrown like a broken set of dominoes over all. A steam tramway—it left the track the only time I used it—was nosing about the hills, but the most prominent features of the landscape were the foundations in brick and stone of a gigantic opera house and the blackened stumps of the pines. California had gone off to investigate on his own account, and presently returned, laughing noiselessly. “They are all mad here,” he said, “all mad. A man nearly pulled a gun on me because I didn’t agree with him that Tacoma was going to whip San Francisco on the strength of carrots and potatoes. I asked him to tell me what the town produced, and I couldn’t get anything out of him except those two darned vegetables. Say, what do you think?” I responded firmly, “I’m going into British territory a little while—to draw breath.”

So Kipling set off for Vancouver, to relax with some of his fellow countrymen. He went by water this time, taking a long boat ride North, through the Sound:

So Kipling set off for Vancouver, to relax with some of his fellow countrymen. He went by water this time, taking a long boat ride North, through the Sound:I took a steamer up Puget Sound for Vancouver, which is the terminus of the Canadian Pacific Railway. That was a queer voyage. The water, landlocked among a thousand islands, lay still as oil under our bows, and the wake of the screw broke up the unquivering reflections of pines and cliffs a mile away. ’Twas as though we were trampling on glass. No one, not even the Government, knows the number of islands in the Sound. Even now you can get one almost for the asking; can build a house, raise sheep, catch Salmon, and become a king on a small scale.

When Kipling docked in Seattle, the city was still in the process of recovering from the Great Fire of 1889. This heavily affected his attitude towards the city:

Have I told you anything about Seattle—the town that was burned out a few weeks ago when the insurance men at San Francisco took losses with a grin? In the ghostly twilight, just as the forests were beginning to glare from the unthrifty islands, we struck it—struck it heavily, for the wharves had all been burned down, and we tied up where we could, crashing into the rotten foundations of a boat house as a pig roots in high grass. The town, like Tacoma, was built upon a hill. In the heart of the business quarters there was a horrible black smudge, as though a Hand had come down and rubbed the place smooth. I know now what being wiped out means. The smudge seemed to be about a mile long, and its blackness was relieved by tents in which men were doing business with the wreck of the stock they had saved. Here were shouts and counter-shouts from the steamer to the temporary wharf, which was laden with shingles for roofing, chairs, trunks, provision-boxes, and all the lath and string arrangements out of which a western town is made.

In June of 1889, to Kipling's relief, he finally made it across the border into British owned Columbia territory, and the city of Vancouver:

Except for certain currents which are not much mentioned, but which make the entrance rather unpleasant for sailing-boats, Vancouver possesses an almost perfect harbor. The town is built all round and about the harbor, and young as it is, its streets are better than those of western America. Moreover, the old flag waves over some of the buildings, and this is cheering to the soul. The place is full of Englishmen who speak the English tongue correctly and with clearness, avoiding more blasphemy than is necessary, and taking a respectable length of time to getting outside their drinks. A great sleepiness lies on Vancouver as compared with an American town: men don't fly up and down the street telling lies, and the spittoons in the delightfully comfortable hotel are unused; the baths are free and their doors are unlocked. You do not have to dig up the hotel clerk when you want to bathe, which shows the inferiority of Vancouver. An American bade me notice the absence of bustle, and was alarmed when in a loud and audible voice I thanked God for it.

The peaceful beauty and gentility of Vancouver had a lasting impact on him, and 15 years later, with money from his novel sales, he purchased a number of plots in and around Van City. Unfortunately not all of these deals were totally legitimate. In later years Kipling found out that a large piece of property in North Van, which he had been paying hefty taxes on, was not actually titled to him! In addition, two small parcels he bough on the East side of Vancouver for $500, he sold over 20 years later for $2,000. This would have been a pretty good deal unless you count the $60 a year taxes he had paid. I guess Vancouverites were just as money hungry as Americans in the end. It was just the spirit of the booming Northwest. Profits were there to be had, but you had to work hard (i.e. lying, cheating, and stealing) to get them.

Kipling's writings about Cascadia give us an interesting insight into the boomtown years of abundant resources, big ideas, and a whole host of individuals looking to cash in. Our cities were built on these foundations, but we should use it as a wary lesson for future progress.

Sources:

- [History and Literature in the Pacific Northwest]: Rudyard Kipling, From Sea to Sea

- [History of Vancouver]: Rudyard Kipling in Vancouver

- [History Link]: Rudyard Kipling visits Seattle

- [Wikipedia]: Rudyard Kipling

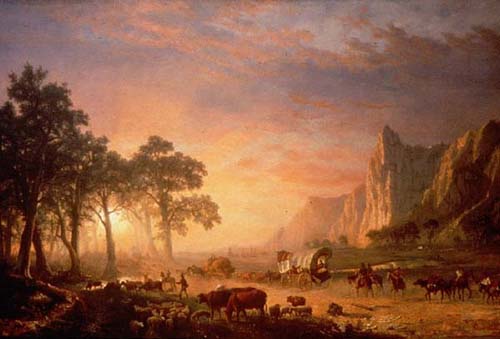

- [Oregon Trail] by Albert Bierstadt, 1869

- [The Willamette River From a Mountain] by Paul Kane, 1847

- [Mt. Rainer] by J. Sykes, 1792

- [Puget Sound on the Pacific Coast] by Albert Bierstadt, 1870

- [City of Vancouver] by Vancouver World Printing, 1898

No comments:

Post a Comment